How tea helped discover silk

Once Upon a Time

A Tradition Begins

Silk was an instant hit. Soft but strong, light and elegant, silk is very adaptable and possesses many virtues that make it extremely valuable. It keeps you cool in the summer and warm in the winter. It wicks moisture. And dyed silk-woven items hold their colour for centuries.

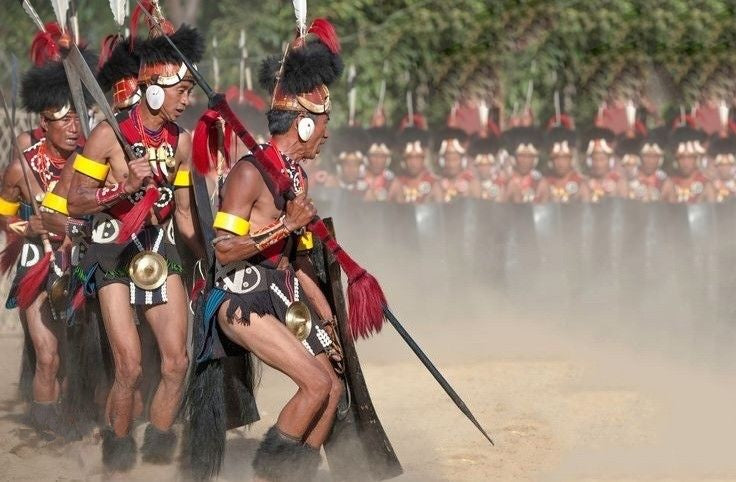

In the first thousand years of its discovery, silk was produced exclusively for the emperor and his close relations or as gifts to dignitaries. In time, as silk production increased, other classes of society were allowed to own silk as well. However, specific colours, accessories, and motifs were exclusive to each social stratum and position. Yellow, for example, was reserved for the emperor. Men from different military ranks also sported different silk headpieces to distinguish themselves.

Other than clothing and decoration, silk was used to make musical instruments, archery bowstrings, fishing lines, and the world’s first (luxury) paper. In fact, much ancient knowledge has been preserved and passed down through silk scrolls. During the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.), silk could even be used as a type of currency in trade.

Throughout the centuries in China’s silk-producing provinces, families of daughters, mothers, and grandmothers would tend to their silkworms for half the year, then harvest, unravel, spin, weave, dye, and embroider during the remaining months.

Spread to the West

Since silkworms were endemic to China and kept a secret from outsiders, foreigners were clueless about how silk was made. But silk quickly became one of the most sought-after fabrics in the world, and many countries were extremely eager to trade for it. This rapid growth in popularity led to the rise of the Silk Road. Although silk products could pass beyond China’s borders, Chinese authorities forbade the secrets of sericulture from leaving the empire. Anyone caught smuggling silk moths or eggs was executed.

After two thousand years of successful border security, however, sericultural knowledge began to trickle into India with immigrants. In 440 C.E., it reached beyond China's western border when a Chinese princess—dispatched to marry a tribal prince as part of diplomatic matrimony—stowed silkworms eggs inside her elaborate up-do. Unfortunately for silk lovers in Europe, the tribal peoples also kept the secret among themselves. The West still had to wait.

At last, in 550 C.E., two monks working for Justinian the Great made it home with the precious eggs hidden in their staffs, and the long-sought knowledge finally arrived in Byzantium. Before then, Romans used to believe that silk was harvested by “removing the down from leaves with the help of water” (Pliny’s Natural History). From there, sericulture gradually spread throughout Europe.

Today, silk is an international commodity, yet the ideals of the orient that lie within silk have never faded. Silk is timeless. And thousands of years ago, it all began with a cup of afternoon tea.